10.20.1 Purpose

Financial analysis is used to understand the financial aspects of an investment, a solution, or a solution approach.

10.20.2 Description

Financial analysis is the assessment of the expected financial viability, stability, and benefit realization of an investment option. It includes a consideration of the total cost of the change as well as the total costs and benefits of using and supporting the solution.

Business analysts use financial analysis to make a solution recommendation for an investment in a specific change initiative by comparing one solution or solution approach to others, based on analysis of the:

- initial cost and the time frame in which those costs are incurred,

- expected financial benefits and the time frame in which they will be incurred,

- ongoing costs of using the solution and supporting the solution,

- risks associated with the change initiative, and

- ongoing risks to business value of using that solution.

A combination of analysis techniques are typically used because each provides a different perspective. Executives compare the financial analysis results of one investment option with that of other possible investments to make decisions about which change initiatives to support.

Financial analysis deals with uncertainty, and as a change initiative progresses through its life cycle, the effects of that uncertainty become better understood.

Financial analysis is continuously applied during the initiative to determine if the change is likely to deliver enough business value such that it should continue. A business analyst may recommend that a change initiative be adjusted or stopped if new information causes the financial analysis results to no longer support the initial solution recommendation.

10.20.3 Elements

.1 Cost of the Change

The cost of a change includes the expected cost of building or acquiring the solution components and the expected costs of transitioning the enterprise from the current state to the future state. This could include the costs associated with changing equipment and software, facilities, staff and other resources, buying out existing contracts, subsidies, penalties, converting data, training, communicating the change, and managing the roll out. These costs may be shared between organizations within the enterprise.

.2 Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

The total cost of ownership (TCO) is the cost to acquire a solution, the cost of using the solution, and the cost of supporting the solution for the foreseeable future, combined to help understand the potential value of a solution. In the case of equipment and facilities, there is often a generally agreed to life expectancy.

However, in the case of processes and software, the life expectancy is often unknown. Some organizations assume a standard time period (for example, three to five years) to understand the costs of ownership of intangibles like processes and software.

.3 Value Realization

Value is typically realized over time. The planned value could be expressed on an annual basis, or could be expressed as a cumulative value over a specific time period.

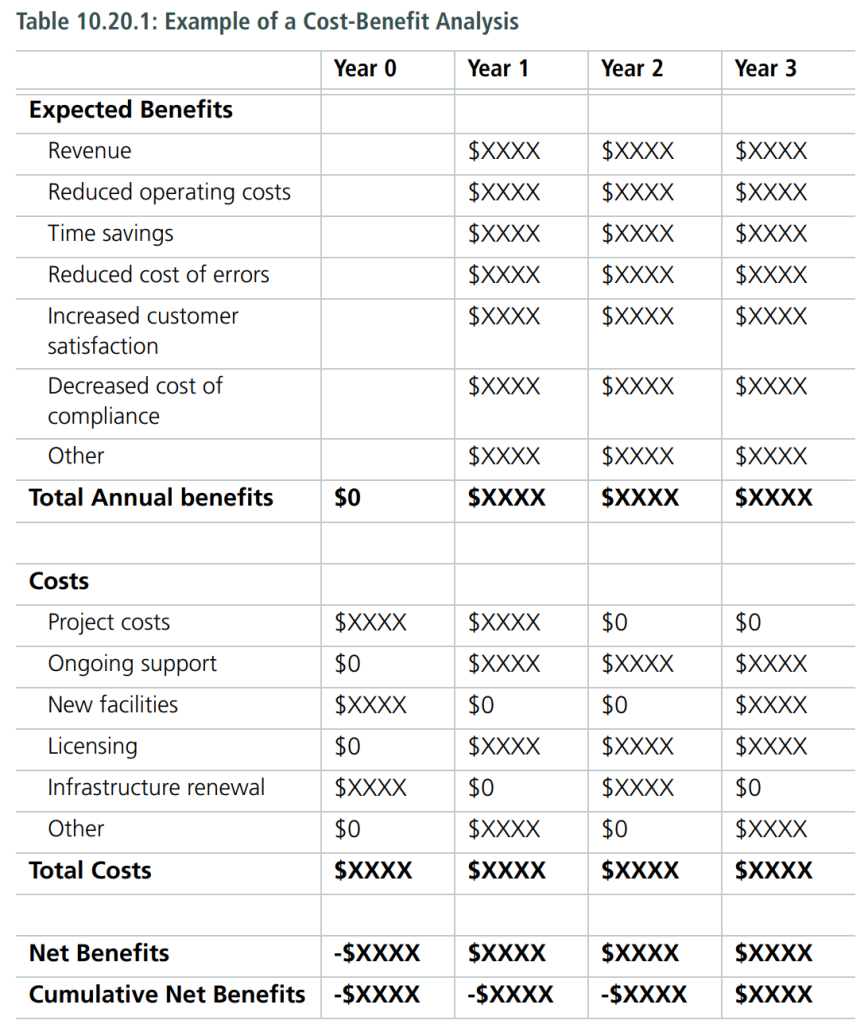

.4 Cost-Benefit Analysis

Cost-benefit analysis (sometimes called benefit-cost analysis) is a prediction of the expected total benefits minus the expected total costs, resulting in an expected net benefit (the planned business value).

Assumptions about the factors that make up the costs and benefits should be clearly stated in the calculations so they can be reviewed, challenged and approved. The costs and benefits will often be estimated based on those assumptions, and the estimating methodology should be described so that it can be reviewed and adjusted if necessary.

The time period of a cost-benefit analysis should look far enough into the future that the solution is in full use, and the planned value is being realized. This will help to understand which costs will be incurred and when, and when the expected value should be realized.

Some benefits may not be realized until future years. Some project and operating costs may be recognized in future years. The cumulative net benefits could be negative for some time until the future.

In some organizations, all or part of the costs associated with the change may be amortized over several years, and the organization may require the cost-benefit analysis to reflect this.

During a change initiative, as the expected costs become real costs, the business analyst may re-examine the cost-benefit analysis to determine if the solution or solution approach is still viable.

.5 Financial Calculations

Organizations use a combination of standard financial calculations to understand different perspectives about when and how different investments deliver value.

These calculations take into consideration the inherent risks in different investments, the amount of upfront money to be invested compared to when the benefits will be realized, a comparison to other investments the organization could make, and the amount of time it will take to recoup the original investment.

Financial software, including spreadsheets, typically provide pre-programmed functions to correctly perform these financial calculations.

Return on Investment

The return on investment (ROI) of a planned change is expressed as a percentage measuring the net benefits divided by the cost of the change. One change initiative, solution, or solution approach may be compared to that of others to determine which one provides the greater overall return relative to the amount of the investment.

The formula to calculate ROI is:

Return on Investment = (Total Benefits – Cost of the Investment) / Cost of the Investment.

The higher the ROI, the better the investment.

When making a comparison between potential investments, the business analyst

should use the same time period for both.

Discount Rate

The discount rate is the assumed interest rate used in present value calculations. In general, this is similar to the interest rate that the organization would expect to earn if it invested its money elsewhere. Many organizations use a standard discount rate, usually determined by its finance officers, to evaluate potential investments such as change initiatives using the same assumptions about expected interest rates. Sometimes a larger discount rate is used for time periods that are more than a few years into the future to reflect greater uncertainty and risk.

Present Value

Different solutions and different solution approaches could realize benefits at different rates and over a different time. To objectively compare the effects of these different rates and time periods, the benefits are calculated in terms of present-day value. The benefit to be realized sometime in the future is reduced by the discount rate to determine its worth today.

The formula to calculate present value is:

Present Value = Sum of (Net Benefits in that period / (1 + Discount Rate for that period)) for all periods in the cost-benefit analysis.

Present value is expressed in currency. The higher the present value, the greater the total benefit.

Present value does not consider the cost of the original investment.

Net Present Value

Net present value (NPV) is the present value of the benefits minus the original cost of the investment. In this way, different investments, and different benefit patterns can be compared in terms of present day value. The higher the NPV, the better the investment.

The formula to calculate net present value is:

Net Present Value = Present Value – Cost of Investment

Net present value is expressed in currency. The higher the NPV, the better the investment.

Internal Rate of Return

The internal rate of return (IRR) is the interest rate at which an investment breaks even, and is usually used to determine if the change, solution or solution approach is worth investing in. The business analyst may compare the IRR of one solution or solution approach to a minimum threshold that the organization expects to earn from its investments (called the hurdle rate). If the change initiative’s IRR is less than the hurdle rate, then the investment should not be made.

Once the planned investment passes the hurdle rate, it could be compared to other investments of the same duration. The investment with the higher IRR would be the better investment. For example, the business analyst could compare two solution approaches over the same time period, and would recommend the one with the higher IRR.

The IRR is internal to one organization since it does not consider external influencers such as inflation or fluctuating interest rates or a changing business context.

The IRR calculation is based on the interest rate at which the NPV is 0:

Net Present Value = (-1 x Original Investment) + Sum of (net benefit for that period / (1 + IRR) for all periods) = 0.

Payback Period

The payback period provides a projection on the time period required to generate enough benefits to recover the cost of the change, irrespective of the discount rate. Once the payback period has passed the initiative would normally show a net financial benefit to the organization, unless operating costs rise. There is no standard formula for calculating the payback period. The time period is usually expressed in years or years and months.

10.20.4 Usage Considerations

.1 Strengths

- Financial analysis allows executive decision makers to objectively compare very different investments from different perspectives.

- Assumptions and estimates built into the benefits and costs, and into the financial calculations, are clearly stated so that they may be challenged or approved.

- It reduces the uncertainty of a change or solution by requiring the identification and analysis of factors that will influence the investment.

- If the context, business need, or stakeholder needs change during a change initiative, it allows the business analyst to objectively re-evaluate the recommended solution.

.2 Limitation

- Some costs and benefits are difficult to quantify financially.

- Because financial analysis is forward looking, there will always be some uncertainty about expected costs and benefits

- Positive financial numbers may give a false sense of security – they may not provide all the information required to understand an initiative.