1.2.5 Focusing on defects can help us plan our tests

Reviewing defects and failures in order to improve processes allows us to improve our testing and our requirements, design and development processes. One phenomenon that many testers have observed is that defects tend to cluster. This can happen because an area of the code is particularly complex and tricky, or because changing software and other products tends to cause knock-on defects. Testers will often use this information when making their risk assessment for planning the tests, and will focus on known “hot spots”.

A main focus of reviews and other static tests is to carry out testing as early as possible, finding and fixing defects more cheaply and preventing defects from appearing at later stages of this project. These activities help us find out about defects earlier and identify potential clusters. Additionally, an important outcome of all testing is information that assists in risk assessment; these reviews will contribute to the planning for the tests executed later in the software development life cycle. We might also carry out root cause analysis to prevent defects and failures happening again and perhaps to identify the cause of clusters and potential future clusters

1.2.6 The defect clusters change over time

Testing Principle – Pesticide paradox

If the same tests are repeated over and over again, eventually the same set of test cases will no longer find any new bugs. To overcome this ‘pesticide paradox’, the test cases need to be regularly reviewed and revised, and new and different tests need to be written to exercise different parts of the software or system to potentially find more defects.

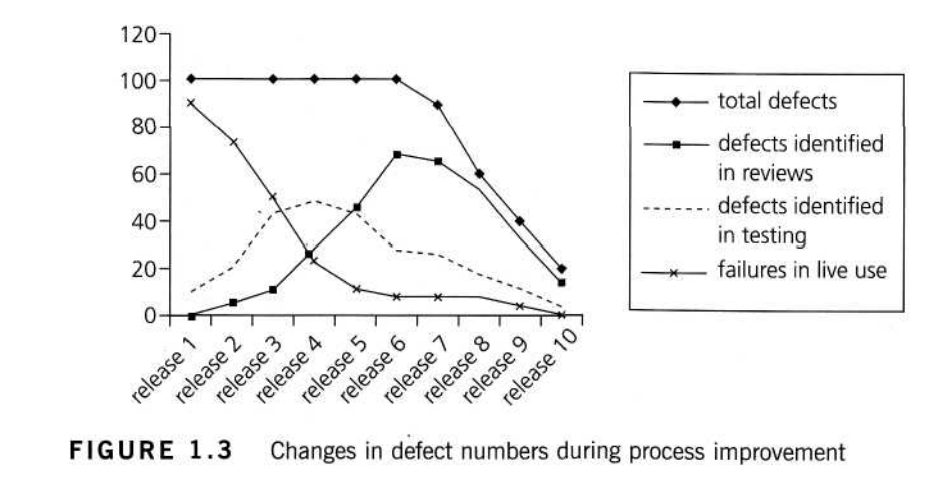

Over time, as we improve our whole software development life cycle and the early static testing, we may well find that dynamic test levels find fewer defects. A typical test improvement initiative will initially find more defects as the testing improves and then, as the defect prevention kicks in, we see the defect numbers dropping, as shown in Figure 1.3. The first part of the improvement enables us to reduce failures in operation; later the improvements are making us more efficient and effective in producing the software with fewer defects in it.

As the “hot spots” for bugs get cleaned up we need to move our focus elsewhere, to the next set of risks. Over time, our focus may change from finding coding bugs, to looking at the requirements and design documents for defects, and to looking for process improvements so that we prevent defects in the product. Referring to Figure 1.3, by releases 9 and 10, we would expect that the overall cost and effort associated with reviews and testing is much lower than in releases 4 or 7.

1.2.7 Debugging removes defects

When a test finds a defect that must be fixed, a programmer must do some work to locate the defect in the code and make the fix. In this process, called debugging, a programmer will examine the code for the immediate cause of the problem, repair the code and check that the code now executes as expected.

The fix is often then tested separately (e.g. by an independent tester) to confirm the fix. Notice that testing and debugging are different activities. Developers may test their own fixes, in which case the very tight cycle of identifying faults, debugging, and retesting is often loosely referred to as debugging. However, often following the debugging cycle the fixed code is tested independently both to retest the fix itself and to apply regression testing to the surrounding unchanged software.

1.2.8 Is the software defect free?

Testing Principle – Testing shows presence of defects

Testing can show that defects are present, but cannot prove that there are no defects. Testing reduces the probability of undiscovered defects remaining in the software but, even if no defects are found, it is not a proof of correctness.

This principle arises from the theory of the process of scientific experimentation and has been adopted by testers; you’ll see the idea in many testing books. While you are not expected to read the scientific theory [Popper] the analogy used in science is useful; however many white swans we see, we cannot say “All swans are white”. However, as soon as we see one black swan we can say “Not all swans are white”. In the same way, however many tests we execute without finding a bug, we have not shown “There are no bugs”. As soon as we find a bug, we have shown “This code is not bug-free”

1.2.9 If we don’t find defects does that mean the users will accept the software?

Testing Principle – Absence of errors fallacy

Finding and fixing defects does not help if the system built is unusable and does not fulfill the users’ needs and expectations.

There is another important principle we must consider; the customers for software – the people and organizations who buy and use it to aid in their day-today tasks – are not interested in defects or numbers of defects, except when they are directly affected by the instability of the software. The people using software are more interested in the software supporting them in completing tasks efficiently and effectively. The software must meet their needs. It is for this reason that the requirements and design defects we discussed earlier are so important, and why reviews and inspections (see Chapter 3) are such a fundamental part of the entire test activity.